I think I would have been more successful in my writing career if I hadn’t had the grandiose idea of submitting material to the top paying publications such as Reader’s Digest, Saturday Evening Post, and Chatelaine. Few things are more de-motivational than rejection. In my teen years I accepted only my mother’s biased assessment.

I think being able to accept rejection and criticism is an important factor in becoming a successful writer. In a previous blog article, I mentioned that one magazine editor suggested I should start writing fiction articles when I had something to say – to experience life before I started writing about it.

He was right for more reasons than he realized. As a teenager I was too young to process rejections successfully. The reasoning part of my brain, the prefrontal cortex, which houses the “executive function,” takes about twenty years to fully develop. As a result, I associated rejection with failure rather than with learning. So, I sulked and stopped writing for months, ignoring the fact that a few editors offered suggestions, and a couple said they would take a second look if I made some changes. The nerve of those editors!

Eventually, I started anew, taking the path of least resistance. I abandoned my dream of being a storyteller, and submitted fillers in the form of true anecdotes, short verse, epigrams, and whatever I spotted being used in various magazines. I wasn’t much of a philosopher in those days, but at least I had a sense of humor, and some knowledge of what teenagers and college students went through. I still recall a few of my earlier submissions to lesser-known publications such as The Link, and American Legion Magazine. For example, two of the verses I recall are:

“The needs of a student at college are known. Pay him a visit but leave them a loan.”

And

“With socks at my ankles I find myself thinking – my mom has the power of positive shrinking.”

When they started being accepted, I learned another lessen regarding rejection. It may initially seem demotivating and demoralizing, but the first acceptance is motivational and exhilarating. There was no holding me back. Rejected pieces rolled harmlessly onto the revision pile like beads of water off a duck’s back.

And to prevent rejections from dampening my hope of a sale, I always had two or three more submissions in the mail before the answers came back on the previous ones.

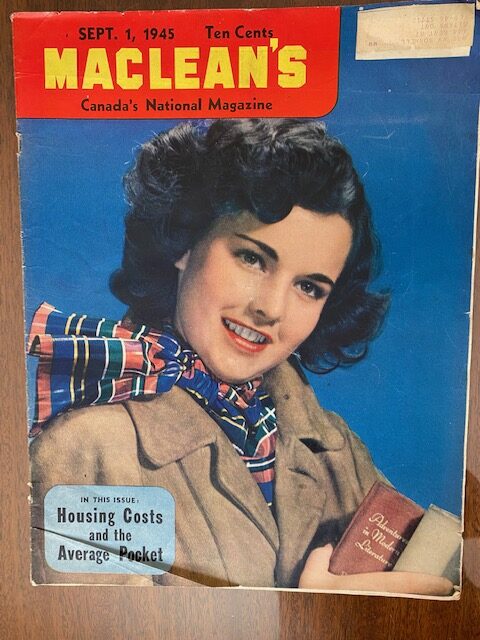

I learned another lesson in rejection from MacLean’s Magazine. MacLean’s Magazine started up long before I was born – in 1905. During the depression, in the 1940s, they added a new section called “Parade.” It was meant “to cheer up the people with a little levity,” according to Suzy Aston and Sue Ferguson, in their article, “MacLean’s: The First 100 years.” As outlined in the article it was “a feature that contained a potpourri of humorous slices of life from across the country.” (MacLean’s is a Canadian magazine written by Canadians for Canadians. A photo of my now vintage September 1st,1945 issue containing the Parade section accompanies this article.)

That was right up my alley, and I submitted very brief stories of happenings – mostly about my father. I made a small fortune (hundreds of dollars in total in those days) talking about him answering the door on Halloween with a hammer from a picture-hanging event still in his hand, and the little goblins scattering in all directions. And the time the stove pipes caught on fire back in the 1940s. It was from the creosote build-up, and our mom ran outside screaming for our father who was picking apples in our tiny orchard. “The house is on fire! The house is on fire!” she yelled. Possessing the exact opposite personality of my “Type A” mother, my dad walked quickly to the house, reached into his pocket for his tobacco and papers, and rolled a cigarette as he observed the red-hot pipes. Saying nothing, he simply hooked a kitchen chair in place with his left foot, climbed on the chair, and calmly lit his cigarette on the pipe. We all knew he was in control of the situation.

I agree, neither scenario was that funny. But the editor of that department, with a few deft changes, made the stories hilarious. My lesson? Don’t ignore the recommendations of an editor who sees hundreds of submissions a month. I had been too busy bemoaning my fate to pay attention to what the editor was saying about my short stories. Success is often in the editing.

I have never heard of a successful writer who has never had a rejection. Stephen King, in his book, On Writing, tells of his first story being rejected with a form letter criticizing his decision to use a staple instead of a paper clip. Did he rant and rave and retire from writing? No. Next time he used a paperclip.

I learned to edit and re-edit, submit and resubmit, study the target publication for the type of fillers they use, and my sales increased. The next market I attacked were the greeting card companies -studio cards only because they accept humor. Rejections didn’t bother me because I had over a dozen more card companies on my list who might accept them. And frequently they did.

By the time I was able to do some serious non-fiction writing, I had the resilience necessary to accept rejection for what it is. A fact of life. And perhaps those “Sorry, your submission does not meet our current editorial requirements,” replies could very well be true. But there are plenty of alternatives.

From fillers and greeting cards I moved to articles and then books, realizing that rejections came with the craft. Even the more well-known writers have also had their articles and books rejected. Such as John Grisham, Stephen King, and J.K. Rowling.

Rejections are the battle scars of writers.

Recent Comments