In my latest book, Making Writing Work for You, I suggest that even if you have an innate talent for writing, you must work just as hard to develop it. I’m convinced that anyone can become a great writer with sufficient perseverance, and purposeful practice. Daniel Coyle, in his book The Talent Code, goes further than that. He uses the story of the Bronte sisters – Charlotte, Emily, and Anne, who produced great works such as Jane Eyre, Wuthering Heights, Agnes Grey, and The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, he suggests that they never had any innate talent. He claimed their first little books were childish and lacked any sign of talent.

Coyle believed that their success was a result of not only an early start and avid interest in both reading and writing, but persistence that continued way past adolescence and into adulthood. Further, he gave credit to the myelin coating of the brain’s neurons. To quote, “Skill is insulation that wraps neural circuits and grows according to certain signals.”

When I started reading books on the brain over 20 years ago, it was thought that myelin, the white coating around the neurons, served as insulation or protection. Then later, it was thought to speed up transmissions within the neurons, and finally that myelin is living tissue following a constant cycle of breakdown and repair. And focused, deliberate practice is what increases the myelin coating.

Yes, anyone can become a great writer, but only a few will be tops in their field because of the motivation, time, effort, and persistence that is required. But the good news is that you don’t need to be born with a talent for writing.

As an example, I always enjoyed writing. But when I became a speaker, I enjoyed that as well. And following the advice I received as a member of the National Speakers Association I selected one topic only – time management. Not only that, but I chose just one speech and rehearsed it to death. The title sometimes changed, but not the content. (I was also told that it’s easier to get a new audience than a new speech.)

Initially, I gave free 90-minute workshops titled “Making Time Work for You.” I sometimes called them “The 90-minute Hour.” I took several years before the talk was good enough to merit a fee. And it took closer to ten years to decide it was time to sell my association management business and go full time as a speaker. I gave the same talk, in varying lengths, over 2000 times during my speaking career.

Over the years, I memorized the speech. Although it was the same speech, no two talks were identical. At first, I adlibbed each one, which allowed me to make improvements each time by either adding or subtracting or changing something. When I accidentally flubbed something, if the mistake got a laugh, I would add it to my next speech. Awkward pauses, stumbles, forgotten lines – everything was fair game if it got a laugh. I would add that new phrase or blunder the next time and the next. I had never heard of “purposeful practice” at that time, so I wasn’t doing it because of those recommended books. The books in the reference list following this article hadn’t been written yet. But I did what those later books recommended – continually improving, getting feedback, correcting, and making changes. What makes a top performer is never stopping your efforts to improve what you are doing, whether it is speaking, writing, organizing, playing the violin, or whatever. In my most recent book, Making Writing Work for You, I give examples of hockey players and others who are now top performers because they never stopped improving.

They all had help from personal coaches or others. In my case it was simply dumb luck. Something else I had learned from years of membership with the National Speakers Association was to see what everyone else who spoke on your topic was doing and do something different. I had been bored so many times sitting in time management seminars, listening to the same old laws, theories, and suggestions. (which are all essential) that I decided to present my ideas through a comedy routine.

A few speakers at NSA and CAPS (Canadian Association of Professional Speakers) said I was a “high risk speaker.” They meant that if my routine went over, it would be fantastic. But if it didn’t, I’d look like an idiot up there on stage. It happened to work. But that’s what the researchers are saying about deliberate practice. Researcher Anders Ericsson defined it as “working on technique, seeking consistent critical feedback, and focusing ruthlessly on shoring up weaknesses.” As Coyle pointed out in his book, Ericsson was referring to the mental state of the top performer. Coyle, as mentioned at the start of this article described the physiological changes involved in the production of myelin.

Either way, one thing I have learned about both speaking and writing; it takes hard work, focus, repetition, and persistence. And that’s true for any skill.

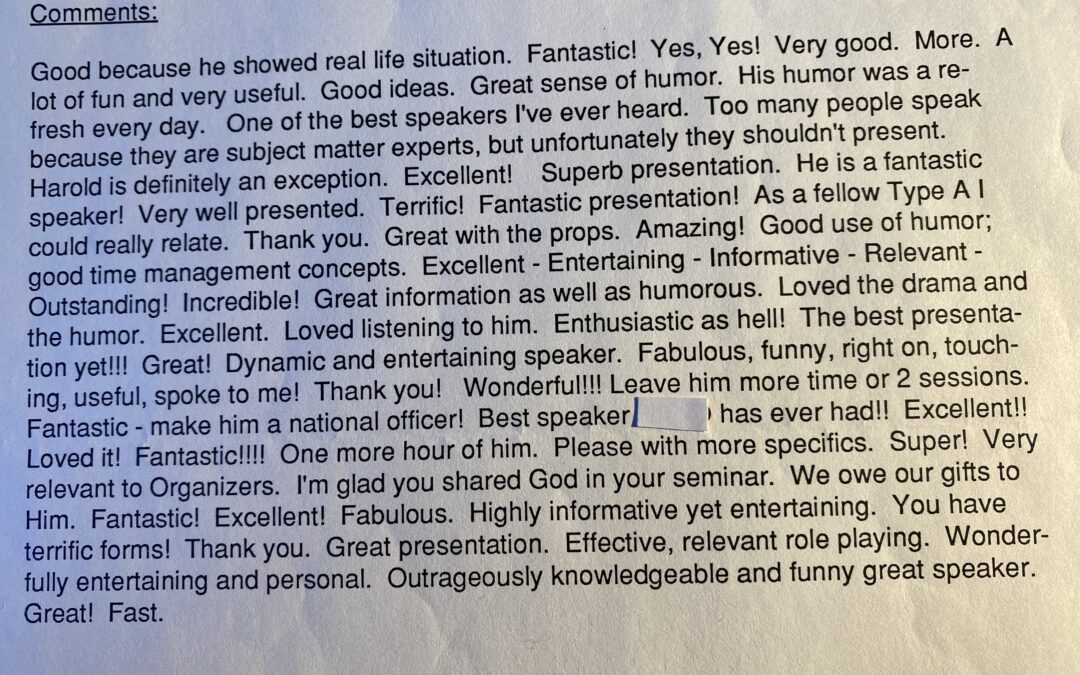

But let’s face it. I’m older now and losing the vim and vigor of my youth. But I can still reflect on the past and do what I am able to do in the future. And if I need a lift, I read the comments of those who attended one of my later presentations at a 1992 conference. Those who attended my presentation rated my performance high on the scale. Not bad for a high-risk speaker. But they didn’t see me ten years earlier when I was giving free speeches. One individual back then said, “You are worth every cent you are charging.” I was thankful for the generous feedback. It helped my speaking career. And it also prepared me for my semi-retirement career – writing. I am no longer able to dance on the ceiling. To be a top performer in writing, you must be immune to rejection. That takes practice as well.

I never did become a top performer in speaking. But I did well, considering it was without access to the information and research results available today. And if I almost did it then, anyone can do it now. Only better.

Here are some reference books to help you learn more about top performance. As for me, I’m going to continue with my writing. My latest book, which had a working title of Confessions of a Part-time Writer, had a title change at the last minute because the editor, who had edited my first book, Making Time work for You, in 1981, thought it would make a good “bookend” to the first one. And the book does describe how I transitioned from speaking to writing in time for my retirement years. But he probably thinks, at my age, that it will be my last one. If so, I intend to prove him wrong. If you want to check it out, it appeared on Amazon yesterday. Click here.

Carter, C. (2017). The sweet spot. Ballantine Books.

Colvin, G. (2008). Talent is overrated what really separates world-class performers from everybody else.

Coyle, D. (2020). The talent code: Greatness isn’t born, it’s grown. Random House Business.

Coyle, D. (2012). The Little Book of Talent. Bantam Books.

Ericsson, A. (2016). Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise. Audible Studios on Brilliance Audio.

Gladwell, M. (2019). Outliers: The story of success. Back Bay Books, Little, Brown and Company.

Schwartz, T. (2016). Way we’re working isn’t working. Simon & Schuster Ltd.

Recent Comments