The Zeigarnik Effect can work against you when you leave a task unfinished, such as working on other projects while there is email waiting to be reviewed. This effect was first observed with servers in restaurants. They seemed to remember everything that each guest ordered until they had been served. Then they quickly forgot who had ordered what. Bluma Zeigarnik, a Soviet psychologist, studied this phenomenon in the 1920s. Unfinished tasks are more securely held in your short-term memory, limiting additional working memory, and causing stress. So, when you switch to another task before the first one is complete, your brain is using up energy hanging onto the memory of the first unfinished task. When you ignore your email in the morning, part of your attention is on the unchecked, uncompleted email while you are working on your priority. This phenomenon is somewhat like attention residue, but while the Zeigarnik Effect is about memory, attention residue is about attention lingering on a previous task. Both cause stress.

The brain loves closure, so it makes more sense to schedule enough time to complete all email messages at one sitting rather than flit back and forth throughout the day. Chris Bailey, in his book, Hyper Focus: How to Manage Your Attention in a World of Distraction, says that the average knowledge worker checks his or her email 11 times per hour – about 88 times over the span of a day.

That’s another reason I spend about a half-hour first thing in the morning checking and dispensing with my email before working for 90 minutes on my priority of the day, whether that is writing, or a different project altogether. Then, after each 90-minute work session, I spend a portion of another half-hour break dispensing with additional email that may have arrived in the interim. That way, fewer emails accumulate in my in-box, and the Zeigarnik Effect, attention residue and retroactive interference – and of course FOMO – are reduced to a minimum. Your performance increases when you have an uncluttered mind just as it does when you have an uncluttered desk and office. And checking email three or four times a day consumes a lot less time than checking it 88 times a day.

You don’t necessarily have to dispense with everything in your in-box. Scheduling a time to do it later, or even adding it to a to-do list, satisfies the brain’s need for closure to a certain degree. But don’t leave it hanging like meal orders in a restaurant waiting to be filled.

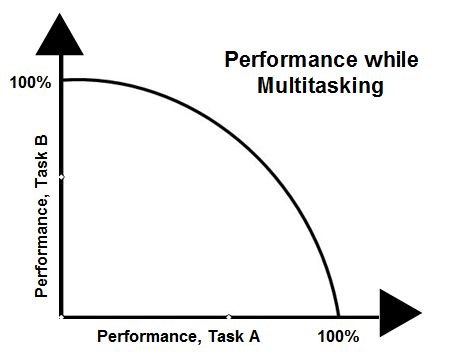

According to researcher Sophie Leroy, it’s never a clean switch when you go from one task to another – such as working for only ten or twenty minutes on a task and then switching to another. The phenomenon called attention residue interferes. What happens is that when you switch from one task to another, a residue of attention remains on the original task. It has been proven by experiments that this attention residue can cause poor performance on the next task. The more you switch back and forth from one task to the next, and the less time you spend on each one, the greater is the negative effect on performance, and the more time is consumed.

That is one reason I recommend working for 90-minute chunks of time on your important projects. Ninety minutes is a reasonable time to maintain focus, and a reasonable time for would-be interrupters to wait for a reply. (Working in snippets of time in waiting rooms or on airplanes is not very productive. It’s better than nothing, although rest and renewal might be a better option.) You have a lot more beginnings and endings if using the Pomodoro Technique, and more occasions for attention residue to take place.

The inefficiency of this “serial multitasking” doesn’t end here. There are other things happening. It has been discovered that “retroactive interference” and “proactive Interference” are at play as well. (They are sometimes referred to as “retroactive inhibition” and “proactive inhibition.”) They seem closely related to attention residue but are distinct phenomena.

Retroactive interference is when new information interferes with the ability to recall previously learned information. It is believed to be one of the causes of forgetting and is important when studying or memorizing information. For example, if you read about one topic, and before reviewing it, start reading a different one, what you had previously read is pushed aside by what you are now reading, and you may have difficulty recalling what you had previously read or how you had thought of using the information. Retroactive interference takes place anytime you switch from one task to another.

Proactive interference is the opposite. It is when old information interferes with the ability to retain new information. For example, when I was teaching memory training, everyone successfully memorized a grocery list of 10 items by linking them together in a story. But if I asked them to remember a second list using the same method, many of them mistakenly included an item or two from the first list.

Another example of proactive interference happens to me whenever I try to learn Spanish. (My son and his family live in Mexico.) When I review the days of the week in Spanish, my previously memorized high school French interferes, and my lundi, mardi, mercredi etc. get mixed up with my lunes, martes, and miercoles. This problem would be much worse if I were to switch from studying one language too soon after practicing a different one. The same problem might occur when studying or memorizing any information that is somewhat like something you had already learned.

And like retroactive interference, it is more prevalent when the switching back and forth is more frequent. That’s why I recommend 90 minutes, and not just 25 minutes as recommended by the Pomodoro technique. And since you have already checked your email, you are keeping the impact of these brain-based phenomena to a minimum. The longer you leave your email unchecked, the more often your mind drifts to that unfinished email, and with each thought of it, you experience attention residue and a flash of FOMO. And the Zeigarnik Effect will ensure that you do keep thinking about it. Oh, and did I mention that the Zeigarnik Effect with its intrusive thoughts of uncompleted tasks can also lead to difficulty sleeping? But that’s for another article.

Editor’s note: This article was excerpted from Harold’s forthcoming book by the same title, Always Check Email in the Morning: And Other Brain-based Strategies.

Recent Comments